Can Competitive Shooting Help Real-World Shooting?

TL;DR. Yes, competitive shooting improves abilities useful in real-world scenarios.

Can Competitive Shooting Help Real-World Combat and Defensive Shooting?

TL;DR. Yes, competitive shooting improves abilities that are useful in real-world scenarios.

Frank Proctor

Affiliation: Way of the Gun

Former Green Beret, USPSA Limited Division Grand Master

Competitive shooting will make a better tactical shooter. The skills necessary to win in competition can also help win in combat. I was a Green Beret for about three years before I started shooting competitively. I was absolutely the tactical shooter that said, “That stuff isn’t real. It’s a game. It doesn’t apply to combat,” etc.

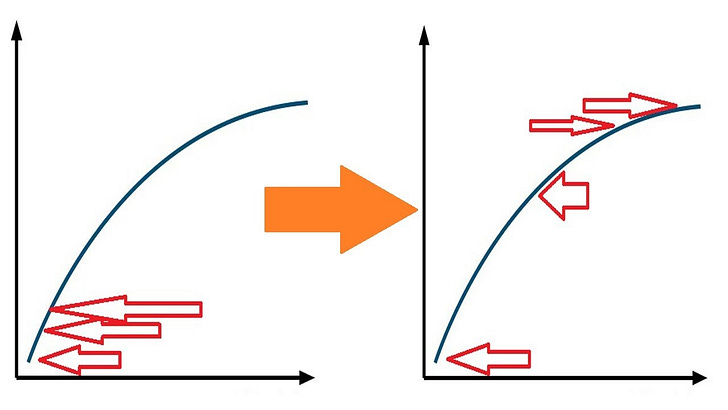

But during my first USPSA match, I found out what I didn’t know about shooting. I wasn’t nearly as good as I thought I was, and I wanted to win, so I trained and competed more and learned more. Some of the skill sets I developed absolutely translate to tactical shooting, including extremely safe gun handling under very dynamic shooting situations, efficiency in movement and mechanics, and the ability to shoot and score hits on targets faster with more accountability. The greatest takeaway for me was more aggressiveness with my vision to see and process information faster. That skill set is key for tactical shooters, as they must see faster and see more in order to make faster decisions. After the decisions are made, then apply the shooting skills that were honed in competitive shooting. Based on my experience I encourage every tactical or defensive shooter to compete often.

Massad Ayoob

Affiliation: Massad Ayoob Group

Position: Director and trainer

Do you think competitive shooting affects real-world defensive-shooting scenarios? Yes, for the better. Why? Competition makes shooting under pressure the norm. Wyatt Earp shot in the informal cow-town matches of his day. In the 20th century, Jelly Bryce was a pistol match winner before he became a cop. Jim Cirillo and Bill Allard of the famed NYPD Stakeout Squad were winning competitions before they became famous for winning shootouts. Col. Charles Askins, Jr. and Kerry Hile in law enforcement, and from Alvin York to Carlos Hathcock in the military … the list goes on.

William Bell

Affiliation: U.S. Customs & Border Protection

Position: Retired CBP officer and instructor

I have been shooting competitively as an Army National Guard officer and law enforcement officer (LEO) for over 38 years and have found that other than force-on-force training using Simunition, shooting competitively provides a certain amount of stress that one doesn’t normally experience in target practice or even during standard LE qualification courses. Competitive shooting builds confidence and results in additional practice than might otherwise not be experienced. This leads to more familiarity with the firearm, so that if there is a weapons-related mishap, the user will have the know-how and “muscle memory” needed to immediately resolve it. Intense practice increases your accuracy, heightens your performance and reduces your reaction time.

There are aspects of competitive shooting that could be counterproductive to “real world” situations, such as firing out in the open or shooting for speed in place of accuracy. But, sadly, lots of the LE training I’ve seen isn’t better as tactics are secondary to qualifying.

If you are serious about shooting to survive, then I think you have enough intelligence to translate what you learn in competition into practical skills for your training toolbox so, if necessary, you can go into action instead of hesitating.

Josh Jackson

Affiliation: LMS Defense

Position: Director of operations and instructor; law enforcement patrol officer

Competitive shooting affects real-world defensive-shooting scenarios in a positive way. In a tactical or defensive environment, your ability to perceive and interpret information faster will directly translate into an ability to make decisions in a compressed time frame. In competitive shooting, participants are required to make decisions in the fastest time possible in an effort to make the highest-value hits, or the most efficient hits. In my opinion, any opportunity to practice getting accurate first-round hits in a compressed time frame is of value for today’s shooters.

Competition requires the shooter to process information as the situation changes in front of you (moving, reactive targets, etc.). Having to make rapid decisions is invaluable training. Other benefits of competitive shooting that will translate to defensive applications include rapid and efficient weapons manipulations, smooth reloads and the ability to clear malfunctions under stress.

A sound mix of defensive firearms training integrating shoot/no shoot targets, compressed time allowances and force-on-force training, coupled with competitive shooting, can only benefit the participant. Every shooter should identify and reevaluate their personal training goals on an ongoing basis. They should then seek out training to help them improve. Seek out information and training from a variety of sources to meet your specific needs.

Gabe White

Affiliation: Public Safety Training Center

Positions: Chief instructor, Public Range FTU

I think the skills tested in competition translate well to defensive shooting in many ways. Competition emphasizes accuracy and speed in shooting and gun handling, on-demand performance under stress and pressure, and making many small mental and physical adjustments while on the fly—all in the honest and open venue of a public contest. No competition accurately reflects the real-world issues of tactics and human interpersonal dynamics. Those cannot be accurately represented in a live-fire competition and must be addressed separately in tactical training. Bad habits can result from the exclusive practice of any activity, whether it’s an exclusive focus on competition or an exclusive focus on tactical training. We can make as big a list of potential training scars one can acquire from tactical training as from competitive shooting.

It is critical to use multiple types of training and adjunct activities—such as dry firing, live fire, force-on-force training, competition, etc.—as often as possible, or there will be holes in our skill sets. The potential downsides of competitive shooting are vastly overblown. Competitive shooting is particularly important because, for most people, it is one of the only circumstances available where there are repeated, legitimate opportunities to perform on demand and under stress. No single activity can give us everything we want or need. It’s important to utilize tactical training to develop our awareness, decision-making skills and tactics, and it can provide a solid foundation for shooting and gun handling, too. Competition is virtually a necessity if our technical skills are to be driven to the highest level possible.

Chris Edwards

Affiliation: Glock, Inc.

Positions: Firearms instructor, GSSF range master/match coordinator

My involvement with competition shooting began over 35 years ago, when, after my first defensive handgun course with John Farnam, I asked what would be a good way to keep my recently acquired skills sharp. John, a follower of Col. Jeff Cooper, said, “Well, there’s this new thing called IPSC.” Since then, I’ve participated in IPSC, USPSA, Steel Challenge, PPC and IDPA and had a hand in getting the GSSF started. I’ve been fortunate enough to receive instruction and training from many respected schools, like Gunsite, Thunder Ranch, the Rogers Shooting School and NRA LE programs. Along with Farnam, I’ve been instructed by Ken Hackathorn, Todd Green, David Blinder, Scotty Reitz, Jeff Gonzales, Michael de Bethancourt, Walt Rauch, Massad Ayoob and privileged to work with Glock instructors and current and recently retired members of the U.S. military’s special operations community. The vast majority of all these good folks have been or are still involved in some form of “practical/action” shooting. In my deputy sheriff days, we would have recognized that as a clue.

Speaking of being a deputy sheriff, I am convinced that my competing improved my shooting, which bolstered my confidence; I was better at my job because of that confidence. Many of the early 20th century gunfighters participated in or started out in competitive shooting—Askins, Bryce, Cirillo and Walsh to name just a few. And recent 21st century warfighters like Harrington, Lamb, Parent and Proctor shoot/have shot competitively—there’s that clue word again.

Here’s the bottom line: Anytime you can get your gear, perform weapons manipulations, see your sights and work triggers in a controlled and safe environment, that’s called learning and experience, and those developed skills are going to be damn helpful should misfortune and evil come your way.

The skills learned while participating in shooting competition certainly transfers to real-life scenarios.

The skills tested in competition translate well to defensive shooting in many ways. Competition emphasizes accuracy and speed in shooting and gun handling, on-demand performance under stress and pressure, and making many small mental and physical adjustments while on the fly—all in the honest and open venue of a public contest. This the reason the military sponsors competitive shooting events and shooting teams such as the Army Marksmanship Unit, Army Reserve Marksmanship Unit, and National Guard Marksmanship Training Unit.

Topic near and dear to the heart!! Army marksmanship has evolved over the years BECAUSE AMUs involvement in Olympic level competitions. Driving past the old quality ranges on post and they all have a barrier ladder beside the old pit. Gunfights are CRAZY fast, and any additional training we give our kids that will go into harms way is beneficial.

At the very leas, competition gives some experience shooting under stress, without people trying to kill you!